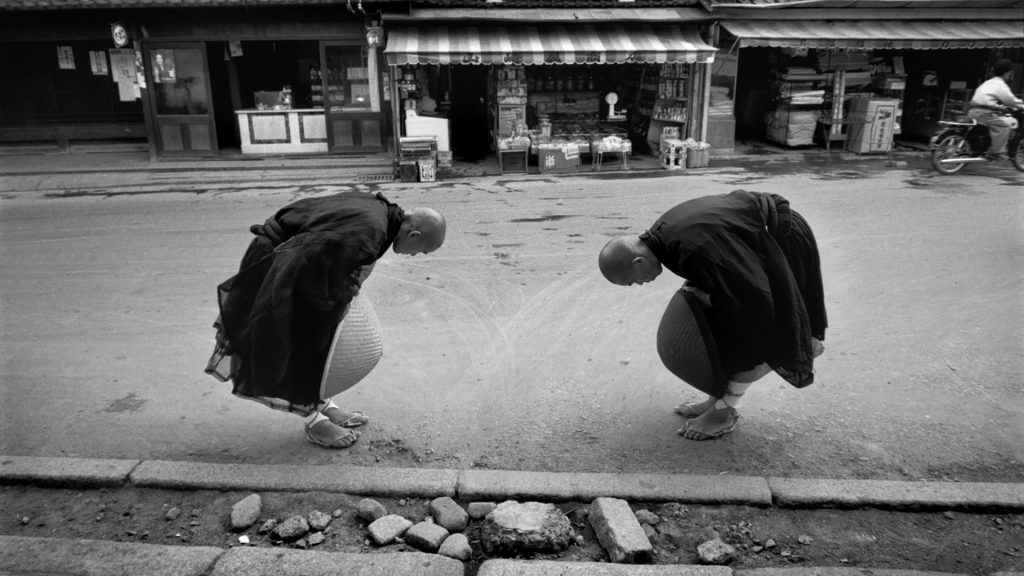

I find as I visit different dojo, that there is a large amount of bowing going on along with a general air of courtesy. However, it is rarely backed up with an understanding of why these practices are being carried out.

Is it really necessary to know the why’s and wherefores in such practices? I would argue that in order to understand our arts as deeply as possible, that the answer is a definitive “yes”.

There should be nothing superfluous in the practice of traditional karate. Everything is done for a reason, and knowing that reason helps one to better carry out whatever it is that one does.

The history behind bowing in karate

Karate master Gichin Funakoshi Sensei was the creator of Shotokan (perhaps the most widely-known style of karate), and a man known as the “father of modern karate.” He wrote a treatise entitled “Niju Kun” (Twenty Principles). In it, he laid out what he saw as twenty rules by which students of karate are urged to follow in an effort to “become better human beings”. The first of these “rules” is “Karate begins and ends with courtesy.”

In a previous article, I talked about the importance in understanding some of the language of those from whom their arts originated. That being said, the Japanese word for courtesy is “reigi”. This word is formed using two kanji characters: 礼 “rei” which is defined as: bow, salutation, salute, courtesy, propriety, ceremony, thanks and appreciation; and 儀 “gi” which is defined as: ceremony, rite or function. Combined, the term “Reigi” can be translate as: ceremonial manners, or etiquette.

In my opinion, proper observance of etiquette should be as much a part of your martial arts training as is learning the techniques.

Reigi is an extremely important part of martial arts practice. In karate, the basic rules come from the formal, highly stylised social systems of Japan. Simply stated, reigi is based on respect, without which martial arts are no different from any other fighting system.

So, let us look at some of the courtesies seen practiced in the traditional karate dojo and offer up some reasoning as to why they occur. Let’s start with the two basic ways of bowing, standing and kneeling.

How to perform a standing bow

There are lots of ways this is properly done (and many more ways it is improperly done). In Japanese systems, the standing bow, (tate rei in Japanese), is performed with hands hanging loosely along the fronts of the thighs. The head is level and in line with the spine. The bow is done without changing the alignment of the spine and head, simply by bending at the hip to an angle of about 30 degrees.

It is often taught that one must raise the head as one bows to “keep an eye on your opponent” (probably based on the scene from the film The Man With The Golden Gun, in which James Bond kicks his opponent as he bows), but this is unnecessary. Performed correctly, one can still observe one’s opponent fully while not moving the head.

NEW! Put the principles from this article into practice with the free courage-boosting MaArtial app on the App Store for iOs and Play Store for Android.

In Chinese systems, this bow is usually accompanied by placing the hands in front of the chest with the palm and fingers of the left hand over the closed fist of the right hand. There are many explanations given to this hand gesture. The simplest being that closed right fist signifying fighting, being covered by the open left hand signifying peace, means the gesture implies a want to not fight, to one that links the hand position to the Shaolin Monks.

It is said that the closed fist represents the sun and the open hand represents the moon: the two brightest bodies in the heavens. Put together, the hands signify that brightness (Ming in Chinese), so it is said in performing this salutation the monks were showing their allegiance to the Ming Dynasty. If one looks at the characters for the sun (日) and the moon (月) when put together to mean bright (明), you could imagine facing someone whose hands were in the salutation one could see those characters portrayed by the hands.

How to perform a kneeling bow

The next bow commonly used is the one performed when kneeling (seiza in Japanese, from the characters 正 (sei), meaning – correct, and 座 (za), meaning seat). Even the act of kneeling down has plenty of things to think about as a martial artist. Is one’s posture correct? Is one’s balance controlled? Are there any openings that could be exploited by an “enemy”?

Thinking of these things as one performs such an innocuous task as kneeling down focuses the mind from the start of the session on the task about to be undertaken: the serious practice of a martial art. The bow performed from seiza is called za rei. Once again, the act of bowing is far more than just putting the hands on the floor and lowering the head. In classical Japanese based systems this is carried out as a samurai armed with a sword would do.

From the kneeling position, with the hands resting on the thighs, the left hand moves first, reaching forward until the fingertips touch the floor in front of the knees in line with the centre of one’s bodyline. Care must be taken not to lean too far forward causing one’s balance to be lost and so requiring the outstretched hand on the floor to prevent one toppling forward. Next the right hand reaches forward to join the left, touching at the fingertips, assuming a pyramid shape between the finger and thumb tips.

The body is then lowered until the elbows touch the floor either side of the knees. Again, one should try to stop your bottom from rising causing a shift in your balance. Carrying out the bow this way lessens the chance of causing an opening, which could be to the advantage of an opponent. To come out of the bow and return to seiza one simply reverses the procedure.

When and why do we bow?

Different systems have different rules as to why and when one bows. But almost martial artists bow to their teachers, seniors and fellow trainees. This is usually performed standing when addressing each other, and before and after partaking in a joint exercise such as sparring. This comes from the fact that the countries that the Asian martial arts originated in all bow in greetings, and this practice continued into training halls.

The difference for a martial artist in the act of bowing is in doing so with what the Japanese call zanshin (残 心, or literally “remaining mind”). This means that when one bows, one’s mind should be focused and fully aware of the person to whom you are bowing and also of one’s surroundings (the bowing opponent in the aforementioned James Bond film clearly demonstrated a complete lack of zanshin, making his bow incorrect).

The bow is intended to show respect to the person you are bowing to, but.to not be aware and think about what you are doing would be disrespectful. My teacher once told me to bow to someone and not feel the need to be fully aware of them showed contempt for their potential.

Spoken words in martial arts etiquette

Most would agree that to not say please and thank you when appropriate is disrespectful. In the Japanese arts, these words are always used before and after training. In the case of bowing to a training partner, prior to beginning working together, it is common to say “Onegaishimasu”. This phrase is difficult to literally translate, but in this instance can be read as “please may I train with you”). Once finished training together, the words “Domo arigato gozaimashita” are said (“thank you very much”, in its most polite form).

While on the subject of spoken words in the dojo, there is a word that is used extensively in training halls and is part of the etiquette of the systems it is used in. That word is “Osu”, a word that has no actual meaning, but is used to mean so much:as a greeting, as an answer to a question, when acknowledging anything, or simply to show spirit. It is not a word used in any classical martial arts dojo though. So where did it come from and why is it so commonly used?

A widely practiced style of karate is Kyokushinkai, founded by Masutatsu Oyama Sensei. This is a powerful system famed for its knockdown competitions and hard training. Practitioners of this system state that osu is a word used by them to convey the thought of perseverance and pushing themselves to the limit. They say that the “os” of osu comes from the kanji characters 押し (Oshi), meaning “push” and the “u” part of the word comes from the characters 忍ぶ (Shinobu), meaning “to endure”.

To covey spirit, this “osu” is shouted strongly much in the same was as “ooh rah” is shouted by the US Marines. I imagine that because of the fame of Kyokushinkai and its fighters, other systems adopted the osu and the usage spread.

Another theory about “osu” suggests that the “osu” is a derivation of the phrase mentioned earlier, onegaishimasu. This seems to me a feasible explanation, given that the formal “onegaishimasu” said so often during karate practice may have become shortened and more aggressive sounding, especially during the militaristic training that took place before the second World War.

Bowing in practice

On entering a dojo, one always bows. In a traditional dojo this bow is towards the shomen (literally “the front”). This is the place where the kamiza (upper seat) is situated. This is the focal point of the dojo, where normally pictures of the founders of a system are found and often where one would find the kamidana (“spirit shelf”, a miniature shrine that in the Japanese Shinto religion is said to house the dojo “spirit”).

Following this initial bow, one should wait at the door until beckoned inside by either a senior student or the sensei. This is both polite, so as to not disturb what is going on, and practical when one considers that in martial arts dojo, there is often weapons practice. To wander in unnoticed could lead to injury by distracting anyone practicing.

Apart from the aforementioned bowing to one’s instructors, seniors and fellow trainees, there are also other bows that are customary at the start and end of all training sessions carried out in Japanese-based systems. In most, there are always at least three bows carried out: one again to “shomen”, one to the sensei, and one to “otagai” (each other).

In the system I practice, there are two further bows carried out. One is to “shinzen” (literally “all spirits”), a a Shinto practice to pay respect to all kami (the “spirits” Shinto followers believe are present in all nature). The other is to “zen hanshi” (“all master teachers”) to show respect to all the teachers that went before and passed down their teachings to us.

I have had conversations with students of various religious persuasions and those of none, about whether bowing to shrines goes against the tenets of their beliefs and ideals. I point out that it is what is in one’s thoughts as one bows that matters. If one does not wish to bow to “spirits”, I tell them they can instead bow to nature, not as in “worshipping” nature, but in appreciation of it and the environment is which the training is taking place.

By taking a bit more time and practicing awareness in your bowing, and thinking about what and why you are doing it, it might actually improve your martial arts practice and perhaps even improve your abilities.

[text-block-start]

At MaArtial, we believe in respect for training partners and to people in daily life. We cannot possibly expect everyone to respect us at all times, but by raising our own standards of

showing respect to others, we can generally pass through the day in an agreeable way.

The article points out the necessity for bowing with respect at the dojo, being fully aware of another person.

This can also be referred to as ” showing presence”. Life coach Tony Robbins is a great advocate for this in married life, for example.

Etiquette in traditional martial arts enhances our empathy for others, and in turn for ourselves.

[text-block-end title=”MaArtial comment”]