“No one is a friend to his friend who does not love in return.” –Plato

Do you always feel the urge to comply with what your friends are doing, when you know you’ll feel better having a quiet night alone?

Or do you cancel last minute, with a text stating “I’m not feeling well”?

Well, Ancient Greece has a thing or two to say about that.

Que Aristotle

Aristotle, has some insights, as he describes in his Nicomachean Ethics:

“Therefore those who love for the sake of utility love for the sake of what is good for themselves, and those who love for the sake of pleasure do so for the sake of what is pleasant to themselves, and not in so far as the other is the person loved but in so far as he is useful or pleasant. And thus these friendships are only incidental.” (129)

The foundations of your friendships are what is at stake here. Do you enjoy another’s company simply as a means to an external satisfaction–e.g. he/she always has the best parties, he/she can always get me a discount on movie tickets–or do you both just have the same hobby? Or, better yet, is it love of the person for him/herself?

For Aristotle, there exist three kinds of friendship: pleasure, utility, and meaning. Excuses exist among friends because we are uncomfortable telling them how we really feel, and, so, they’re a great indicator of just how we might feel about particular friendships. At some point, we must all question why we’re friends with the people we call friends.

If you’re inclined towards “meaning”, surely there’s no need to use excuses. After all, friendship with another simply because of whom they are should push you towards being honest with him/her. But, if you see some cognizant dissonance in your relationship here–a friendship based on meaningful connection while you constantly have to search for excuses–maybe it’s time for a little more introspection

Utility, Pleasure, and Meaning

What exactly is the difference here? Let’s break it down in simple terms:

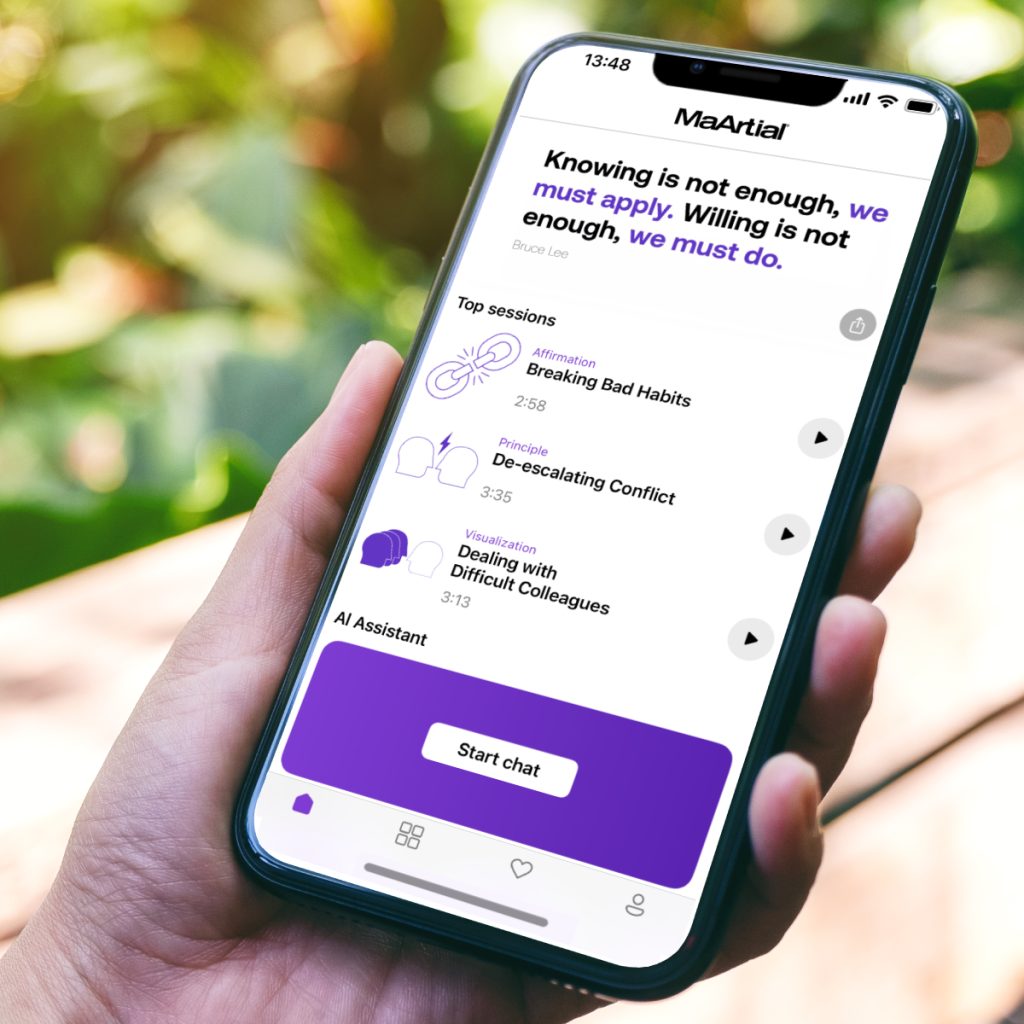

NEW! Put the principles from this article into practice with the free courage-boosting MaArtial app on the App Store for iOs and Play Store for Android.

Pleasure: Their company is pleasant, and you enjoy them for what they do. They’re funny, know how to make you feel comfortable, you guys have the same hobby, etc.

Utility: They can get you what you want, and you like to have them around for their connections.

Meaning: Philia, in Greek. The deepest of them all–and the rarest–from those who offer that spiritual, deep connection we crave as we grow older.

According to Aristotle, the first two lack duration; these friends are not liked for themselves, and, because our desires change with time, they will fade away. Friendships based on meaning, however, are those based on truth and are what he termed “perfect”:

“Perfect friendship is the friendship of men who are good, and alike in virtue; for these wish well alike to each other qua good, and they are good themselves…The friendship of the good too and this alone is proof against slander; for it is not easy to trust any one [word] about a man who has long been tested by oneself; and it is among good men that trust and the feeling that ‘he would never wrong me’ and all the other things that are demanded in true friendship are found. In the other kinds of friendship, however, there is nothing to prevent these evils arising.” (130-131)

Aristotle’s understanding of a virtuous friendship–which echoes that of Confucius’s Rán just a century earlier–is based on a shared belief in morality and values that two people share. Thus, there’s a level of fulfilled justice (in other words–no lies and no excuses) that pervades these relationships:

“…it is a more terrible thing to defraud a comrade than a fellow-citizen, more terrible not to help a brother than a stranger, and more terrible to wound a father than anyone else. And the demands of justice also seem to increase with the intensity of the friendship, which implies that friendship and justice exist between the same persons and have an equal extension.” (137)

Choose Wisely

So, if you have found a friendship that you would consider meaningful, Aristotle would ask, “What reason is there to give an excuse? What would you have to gain from lying for no good reason to a just friend?”

And, conversely, if you do have friendships in which excuses and complaints are prevalent–most often friendships of utility– why stay in them?

“Complaints and reproaches arise either only or chiefly in the friendship of utility, and this is only to be expected…complaints [do not] arise much even in friendships of pleasure; for both get at the same time what they desire, if they enjoy spending their time together; and even a man who complained of another for not affording him pleasure would seem ridiculous, since it is in his power not to spend his days with him.” (142-143)

So, like Confucius before him, Aristotle advises to seek a virtuous approach but with a pragmatic stance: if you do enter into a friendship of utility or pleasure, understand the consequences.

“Most people seem, owing to ambition, to wish to be loved rather than to love; which is why most men love flattery; for the flatterer is a friend in an inferior position, or pretends to be such and to love more than he is loved; and being loved seems to be akin to being honoured, and this is what most people aim at.” (136)

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by W.D. Ross. Batoche Book, 1999.